Beginning in the 1910s, thousands of African Americans left the South and headed North and Midwest in search of better lives and to escape racial violence. The First World War further fueled this migration, as the mobilization of men for the frontlines created a labor shortage. Between 1910 and 1920, Chicago’s Black population more than doubled, growing from approximately 44,000 to nearly 110,000 people. This rapid population increase led to competition between African Americans and white workers for jobs. The situation worsened in 1919 as millions of soldiers returned from the warfront. This tension culminated in an eruption of racial violence known as the “Red Summer.” Here, we delve into the events that unfolded in Chicago during this period, as detailed on chicago-yes.com.

The Black Belt in Chicago

Housing segregation, reinforced by banks, real estate agents, native Chicagoans, and ethnic street gangs, led to an increasing number of Black residents moving into a 31-block strip on the South Side, known as the Black Belt. This area quickly expanded, developing its own social and economic stratification. The poorest African Americans lived in the northern part of the Belt, while wealthier Black residents occupied the southern section.

Living conditions in the Black Belt were appalling due to severe overcrowding. At the onset of the 1900s, African Americans who participated in the Great Migration sought refuge there. Within ten years, the city’s Black population had more than doubled. This influx marked significant demographic changes in Chicago. While African Americans made up 11% of the South Side’s population in 1910, they accounted for 24.6% by 1920. As new arrivals streamed into the Black Belt, the city also faced a post-war housing shortage.

Despite the Black Belt’s proximity to jobs at steel mills and meatpacking plants, unbearable living conditions drove Black residents to seek housing in other areas of the city. Those who managed to purchase or rent homes in predominantly white neighborhoods bordering the Black Belt were seen as “intruders,” and their presence often resulted in declining property values.

These “Black pioneers,” the first African Americans to move into white neighborhoods, often suffered from arson, property destruction, threats, and violence. Between 1917 and 1919, there were about 24 recorded cases of arson.

In Chicago, as in other cities, African Americans’ lives were governed by segregation policies and practices. Job competition sparked tensions and racial dominance. Black workers, who moved north to work in factories, were often cast as strikebreakers and excluded from labor unions. White ethnic groups, including Italians, Poles, and Greeks, banded together in social clubs and gangs to defend their rights and assert dominance over others.

A Fateful Sunday

Sunday, July 27, 1919, was an extremely hot day, with temperatures soaring to 95°F (35°C). That fateful day, African Americans went to the “Black beach” at 25th Street, while white residents gathered at the “white beach” on 29th Street. White gangs closely monitored the shoreline to ensure that Black residents did not cross the boundary.

Eugene Williams, a Black teenager, along with his friends, decided to swim that day. Born in Georgia on March 10, 1902, Williams moved to Chicago’s Black Belt with his family when he was six years old. After finishing school, he worked as a delivery boy at a grocery store.

While swimming, Williams and his friends accidentally drifted past the boundary between the segregated beaches. A white man, George Stauber, noticed and began throwing stones at the boys. One of the stones struck Williams in the head, causing him to fall off the raft and drown. Williams’ friends tried to get a Black police officer to arrest Stauber, but a white officer intervened, ultimately arresting someone from the Black crowd instead.

“Deadly Carnival”

The news of the drowning quickly spread along the beaches. By around 4:00 PM, a thousand Black residents gathered at the 29th Street beach. A fight erupted, and the tension escalated into a horrific six-day race riot, the worst in Chicago’s history. Hundreds of Black and white Chicagoans stormed the beach, and the situation quickly spiraled out of control. James Crawford, a 37-year-old Black man who shot and wounded a white officer, was shot dead by another officer at the scene. By 6:15 PM, the riots had intensified, turning the 29th Street beach into “ground zero.” Within hours, the death toll had reached 43.

The riots rapidly spread throughout the South Side. Within two hours, they engulfed southwestern Chicago, the West Side, and the Loop. Gangs of white men and boys, armed with guns and baseball bats, began terrorizing the city. Some gangs, numbering 200 to 300 individuals, painted their faces black to give the impression that Black residents were inciting the violence. In response, African Americans armed themselves with knives and guns, defending their homes and families. Police officers attempted to restore order by firing into the crowds. Provident Hospital, founded by an African American surgeon and located in the heart of the Black Belt, was filled with injured and dying people within hours.

Government Inaction Leads to Tragedy

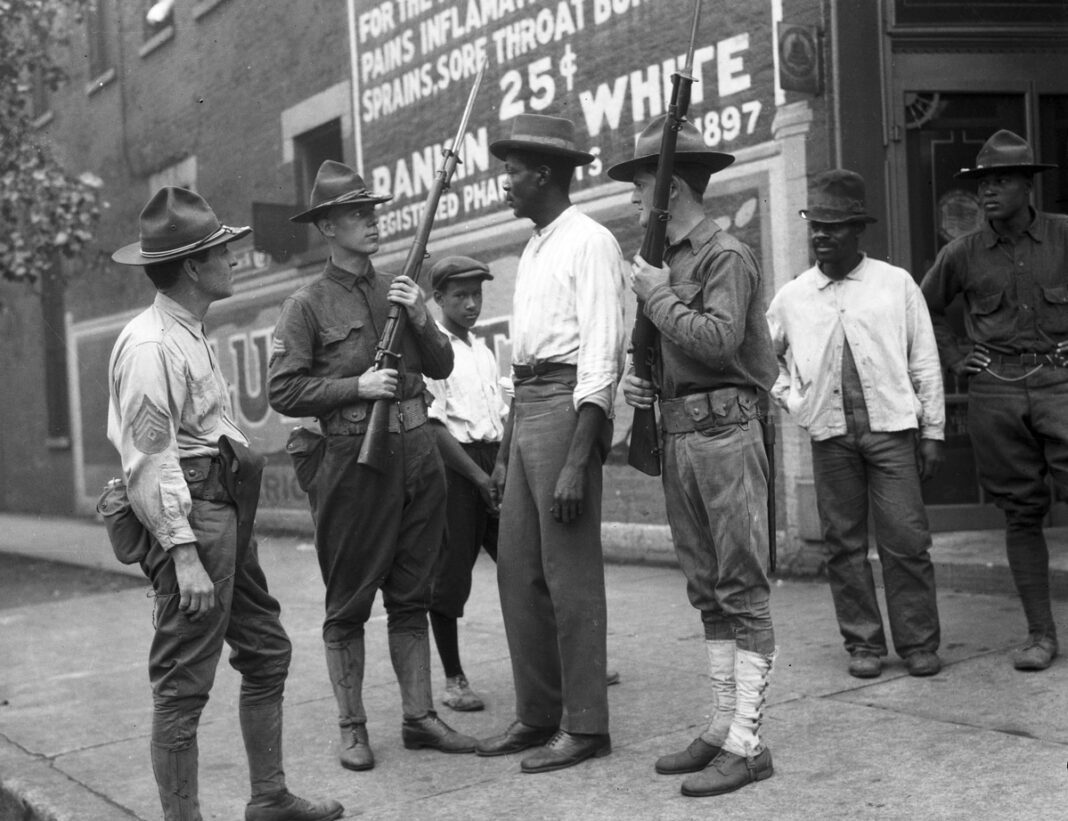

The city government, led by Superintendent of Police John J. Garrity and Mayor William Thompson, refused to request military assistance. They ignored complaints that the city’s police force was incapable of handling the riots. Governor Frank Lowden followed suit, waiting for the city’s request for help. A few days after the drowning incident, when it became clear that the riots would not end without external intervention, the National Guard was called in. Although a police force of about 5,000 to 6,000 officers was placed on alert by Monday evening, decisive action wasn’t taken until Wednesday morning.

During the riots, many African Americans were forced to hide in their homes, unable to get to work, access food, or earn any money. Meatpacking plants set up payroll distribution points at community organizations so that roughly 6,000 workers could receive their wages. Banks in the Black Belt provided small loans of $1 to $3, while the Red Cross distributed food to Black families.

The riots continued for nearly two weeks. In total, 537 people were injured, and 38 were killed. Of those killed, 23 were African Americans, and 324 individuals suffered serious injuries. Approximately 2,000 people were left homeless due to arson and other acts of vandalism. After the situation was stabilized, the victims of the riots sued the city. In 1923, Eugene Williams’ father was awarded $4,500 in compensation.

Neither the riots nor segregation deterred African Americans from moving to Chicago. Today, the racial profile of the city differs from that of 1919. Of Chicago’s 2.7 million residents, 33% are African American.

Source:

- https://dusablemuseum.org/exhibition/troubled-waters-chicago-1919-race-riot/

- https://interactive.wttw.com/playlist/2019/07/26/chicago-1919-race-riot

- https://www.theworldwar.org/learn/about-wwi/red-summer

- https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2021/2/18/dying-to-swim-in-chicago-race-riots-and-the-red-summer-of-1919