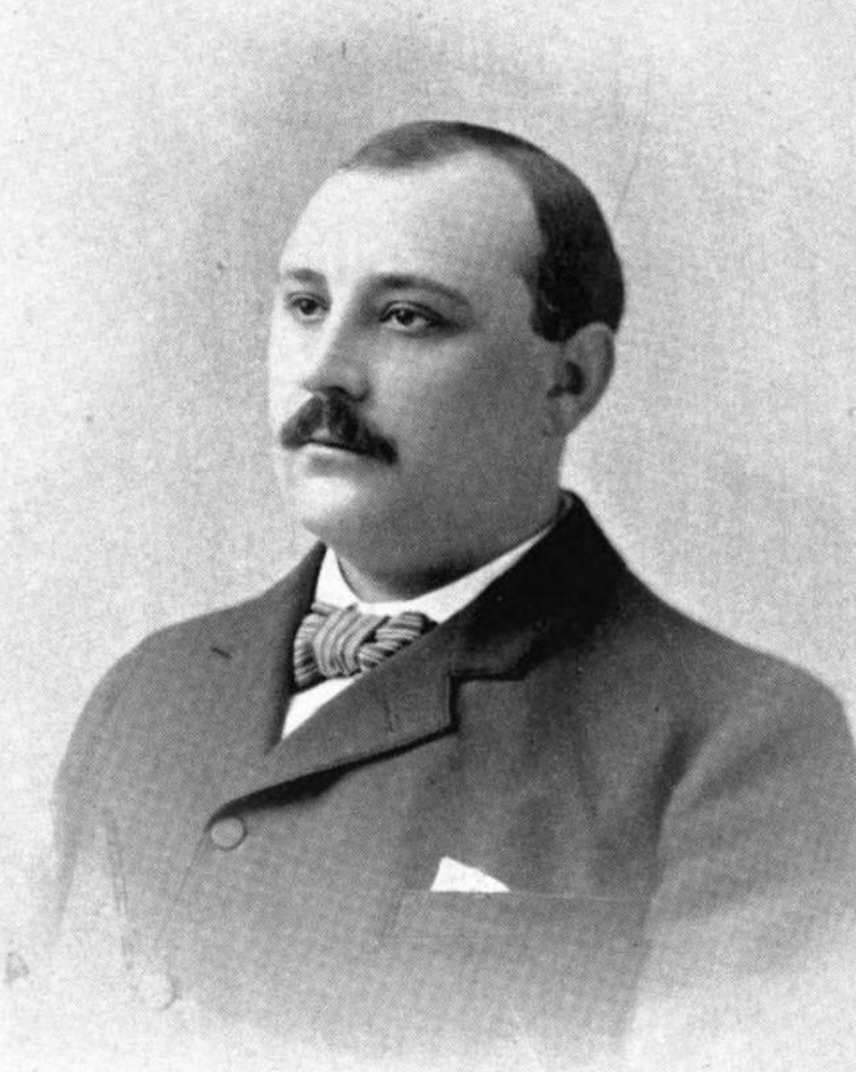

He went down in Chicago history as one of the most controversial mayors of the early 20th century. His journey, from a humble court bailiff to the leader of one of the largest cities in the United States, was a reflection of ambition, political intrigue, and the complex relationship between power and the criminal underworld. Despite the corruption scandals, his term saw the start of the famous Plan of Chicago, which shaped the city’s architecture for decades to come. Read more at chicago-yes.

Professional Career

Busse began his professional life as a court bailiff. He worked in Judge Theodore Brentano’s courtroom, notably during the high-profile trial of Patrick Eugene Prendergast—the assassin of Mayor Carter Harrison III. This period provided Busse with his first taste of the justice system and a pathway into Chicago’s political circles.

His political career took off within the Republican Party. He was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives in 1894 and 1896, and by 1898, he had become a state senator. Following this, his political influence led him to the position of Illinois State Treasurer, which he held starting in 1902.

In 1905, President Theodore Roosevelt appointed Busse as the Postmaster of Chicago—a position that was both political and influential in the city’s hierarchy at the time. Alongside his political endeavors, Busse was involved in business, serving as secretary and treasurer of the Northwestern Coal Company until 1905.

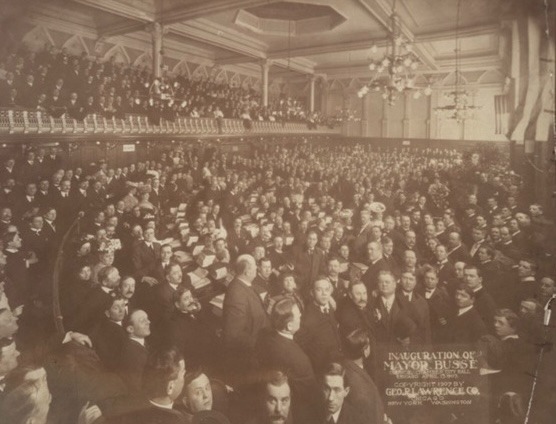

The 1907 Election Victory

In 1907, Busse defeated the incumbent Democratic Mayor Edward F. Dunne and took the city’s top office. The inauguration ceremony took place on April 15 of that year.

His rise to power was accompanied by expectations of renewal and reform, as the Republicans positioned themselves as an alternative to the Democratic governance approaches of the era. However, the events of the following years largely shattered those hopes.

Tenure in Office

Mayor Busse’s term was marked by widespread corruption. He maintained political ties with several influential figures in organized crime. His name was frequently used to advertise questionable establishments, including brothels, which only amplified public outcry.

In response to the rise in crime and moral decay, various civic movements began to form, aimed at cleaning up City Hall. In March 1910, Mayor Busse appointed a 30-member commission of Chicago representatives to investigate prostitution and illegal gambling. The commission’s experts, which included civic and religious leaders, concluded that the system for regulating the “vice district” was outdated and proposed radical reforms. The commission’s report, published in 1911 under the title The Social Evil in Chicago, contained statistical data on prostitution and 96 recommendations for improvement. The Chicago Tribune credited Busse for establishing this first municipal commission for the scientific study of the city’s “social evil.” His own reaction to the accusations was quite bold: Busse openly admitted to spending evenings at the “J. C. Murphy” saloon on Clark Street and saw no problem with it.

Despite the shadows of corruption, Frederick A. Busse made one of the most significant contributions to the city’s development. He championed the Plan of Chicago—an ambitious project that defined the metropolis’s architectural and infrastructural future. On July 4, 1909, he approved the idea of creating a commission for its implementation. On November 1, 1909, the Chicago City Council approved the composition of the Chicago Plan Commission—328 influential citizens of the city were appointed at Busse’s initiative. Charles H. Wacker was named the commission’s first chairman, with Busse’s support. Under the commission’s auspices, “Wacker’s Manual” was created, a textbook for Chicago schools, intended to educate the youth on the vision of the plan—a strategic tool for public awareness. Thanks to the commission’s actions, 86 bond issues related to the Plan project were passed between 1912 and 1931, covering about 17 different city initiatives.

Busse attempted to run for re-election in 1911 but lost to Democrat Carter Harrison IV. He officially left the mayor’s office on April 17, 1911. Carter Harrison IV had a significant political pedigree. His family had been actively involved in Chicago politics for decades, and he enjoyed the support of various civic and business groups. His campaign effectively capitalized on public dissatisfaction. The city traditionally had a strong Democratic base at the time. After the long rule of the Republican Busse, voters were eager for a change in political direction. His image as a “machine politician,” even with his support for the Plan of Chicago, failed to persuade enough voters.

Frederick A. Busse died on July 9, 1914, at the age of 48 from a heart valve condition. He was buried at Graceland Cemetery—one of Chicago’s most famous burial grounds, where many influential civic and political figures rest. He left behind a complicated legacy. His name is associated both with widespread corruption and ties to the criminal element, as well as with vital urban planning initiatives that influenced Chicago’s future. Busse’s figure exemplifies how political ambition can be intertwined with scandal, and significant reforms can coexist with shady dealings and a controversial reputation.