World War II left a painful mark on Chicago and its residents. It claimed countless lives, orphaned children, and shattered people’s futures. From the fall of 1939 to early December 1941, a fierce debate raged in Chicago over whether Americans should enter the war in Europe. Chicago Tribune publisher R. McCormick led the isolationists, while Daily News owner Frank Knox championed the interventionist view. Ultimately, the war’s devastating impact was unavoidable. A vast number of Chicagoans were drafted into the military. Those who remained on the home front attended rallies, endured rationing, planted victory gardens, and volunteered. Learn more about Chicago during World War II at chicago-yes.com.

A Few Statistics

World War II is considered the deadliest conflict in human history, involving more than 50 countries. It was partly fueled by the economic crisis of the Great Depression and the political tensions left unresolved after World War I.

In 1939, Nazi Germany invaded Poland, and the conflict soon spread across the globe, with fighting lasting until 1945. The war is estimated to have claimed the lives of 60 to 80 million people, including 55 million civilians. Numerous cities across Europe and Asia were left in ruins.

The War Effort in Chicago

From the first days of the war, about 20,000 dedicated block captains across the city held send-off ceremonies for those leaving to serve and erected small shrines for those who did not return. Residents united to conduct civil defense drills and collected scrap metal, paper, rubber, and grease for the war effort, with some materials being recycled into nitroglycerin.

The war instantly transformed the city’s employment landscape. Chicago’s diverse industrial base allowed it to rank second only to Detroit in the value of manufactured war goods, producing an estimated $24 billion worth of materials. Over 1,400 companies produced everything from field rations to parachutes and torpedoes. New aircraft factories employed 100,000 people to manufacture engines, aluminum sheets, bombsights, and other vital components. The Douglas plant, located on the site of today’s O’Hare Airport, produced 654 C-54 Skymaster transport planes in just 25 months. Remarkably, more than half of all military electronics used during the war were produced in 60 local factories. Even with Chicagoans working double shifts, this massive output quickly led to labor shortages. To fill the gap, the disabled, the elderly, and tens of thousands of women joined the workforce. They were joined by some 60,000 African Americans arriving from the South and an equal number of Japanese Americans released from desert internment camps. City schools and universities then ran around-the-clock training programs to equip these new workers with necessary skills.

Training in Chicago

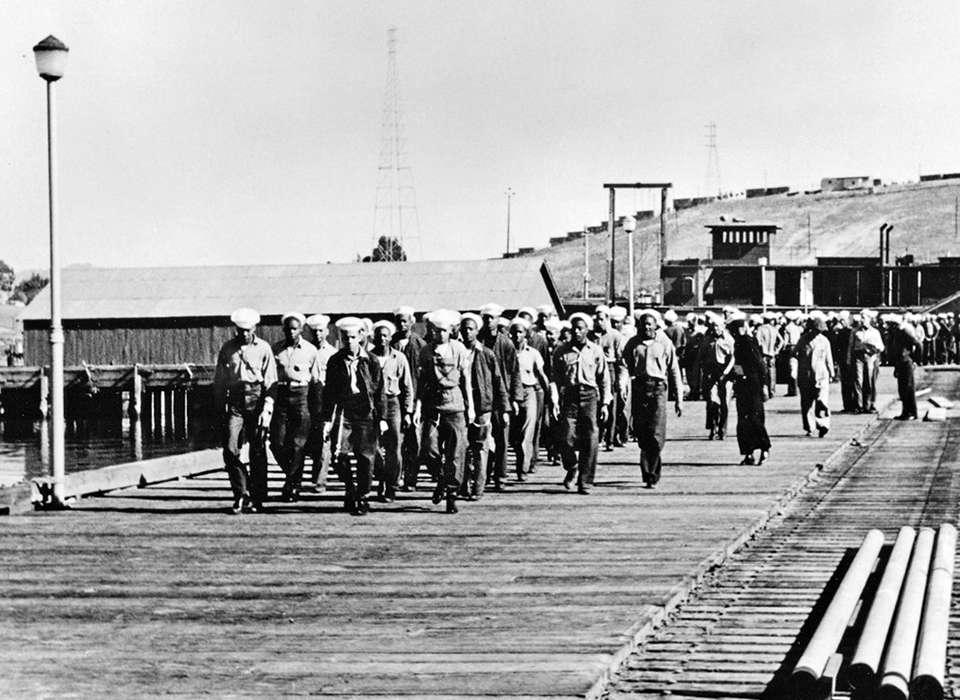

The Great Lakes Naval Training Station near Chicago became the boot camp for a third of all personnel serving in the U.S. Navy, while Fort Sheridan became a major Army training center. The Glenview Naval Air Station graduated 20,000 carrier pilots, who trained on two old lake steamers that had been converted into aircraft carriers. An equal number of officers graduated from Northwestern University’s Naval Midshipmen’s training program. Additionally, specialized training was conducted in electronics, meteorology, naval engineering, espionage, and foreign languages. Tens of thousands of military personnel passing through the city by rail were welcomed by Chicago’s service centers. For example, the centers at 176 Washington Street and in the Auditorium Building had served 24 million meals by the end of the war.

After World War II ended, Chicago’s powerful industrial and economic growth continued.