Chicago played a crucial role in the Civil War, and in turn, the war had a profound impact on the city’s development. Learn more about this history at chicago-yes.com.

Why Did the Civil War Begin?

The American Civil War was fought between the United States (the Union) and the Confederate States, a coalition of 11 Southern states that seceded from the Union in 1860-1861. The conflict erupted over long-standing disagreements about the institution of slavery. In February 1861, members of the Confederate Constitutional Convention elected Jefferson Davis as the president of the Confederate States of America. After four bloody years of conflict, the United States defeated the Confederacy, and the institution of slavery was abolished nationwide.

By the mid-19th century, slavery was concentrated primarily in the Southern states, where enslaved people were used for agricultural labor and as domestic servants. Many people in both the North and South viewed slavery as morally wrong, which created deep divisions in the political and social landscape. Southerners felt threatened by Northern politicians, arguing that the federal government was determined to end slavery. For years, politicians had sought compromises to avoid a national split, but when 11 states seceded to form the Confederacy, war became inevitable. The conflict began over federal forts in the South. President Lincoln attempted to resupply the garrisons by sea, but the Confederacy demanded their surrender. When U.S. soldiers at Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor refused, South Carolinians bombarded the fort. After a 34-hour battle, the Union soldiers surrendered.

A Surge of Volunteers

According to various sources, more than 22,000 men from Cook County served in the Union Army during the Civil War. Support for the Union was strong throughout Chicago and its surrounding counties. Enthusiasm for the war was so high that a draft was rarely needed; men eagerly volunteered, encouraged by recruitment rallies and substantial bounties. However, Chicago’s active support came at a steep price. Over 4,000 soldiers from the city died during the war.

Among those who gave their lives was Colonel Elmer Ellsworth, the first Union officer killed in the conflict. He commanded the 11th New York Volunteer Infantry, known as the “First Fire Zouaves.” Before the war, he had worked as a law clerk for Abraham Lincoln and became a close friend. When Lincoln was elected president, Ellsworth followed him to Washington. He then went to New York City, where he formed his regiment from volunteer firefighters. On May 24, 1861, Ellsworth and his men entered Alexandria, Virginia, where they saw a large Confederate flag flying above the Marshall House hotel. As Ellsworth took the flag down, the hotel’s owner, James W. Jackson, shot and killed him. Lincoln was devastated by his friend’s death. The slogan “Remember Ellsworth!” became a rallying cry for the 44th New York Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

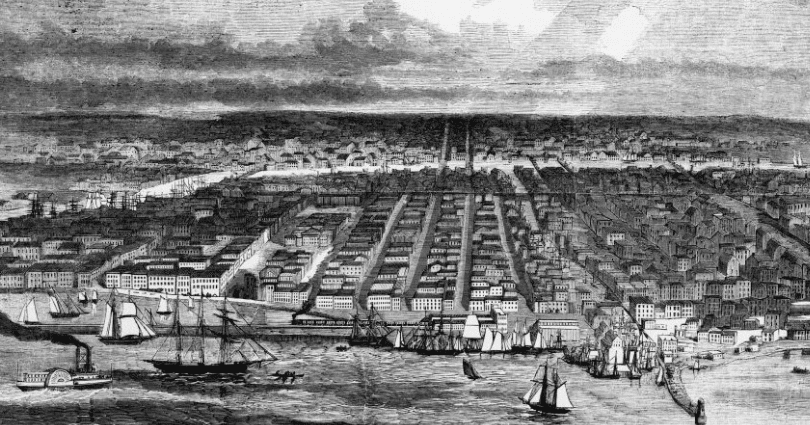

Chicago: A Hub of Industry and Commerce

In the early years of the Civil War, Chicago’s rivals—St. Louis, Missouri, and Cincinnati, Ohio—were located too close to the front lines, and their trade on the Mississippi and Ohio rivers was frequently disrupted. Thanks to its strategic central location and extensive railroad network, Chicago became the undisputed center for meatpacking, wheat, lumber, and other industries. The city also supplied a vast amount of weapons and provisions to the Union Army, becoming the second-largest supplier in the nation, surpassed only by New York City.

Advanced Banking and Abolitionist Sentiment

The city’s banking sector achieved stability during the Civil War. The First National Bank of Chicago was founded in the summer of 1863. By 1865, the city had more than half a dozen national banks, more than any other American city at the time. The capital accumulated by these banks fueled Chicago’s further industrialization in the latter half of the 19th century.

Chicago also had a strong reputation as a center of abolitionist activity. Local abolitionists ranged from formerly enslaved people to evangelical Christians. Before his famous raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, John Brown and his fellow abolitionists stayed at the home of John Jones, a wealthy Black tailor. Organizations like the Chicago Anti-Slavery Society and the Chicago Female Anti-Slavery Society worked closely with religious abolitionist groups. In 1862, several local churches even sent a delegation to President Lincoln to urge him to implement a policy of emancipation. Many saw the city as a launchpad for Lincoln’s political career, and some even blamed Chicago for starting the war. The Chicago Tribune gained national prominence before the war and became one of the leading Republican newspapers of the era.

Support for the Union and a Famous Song

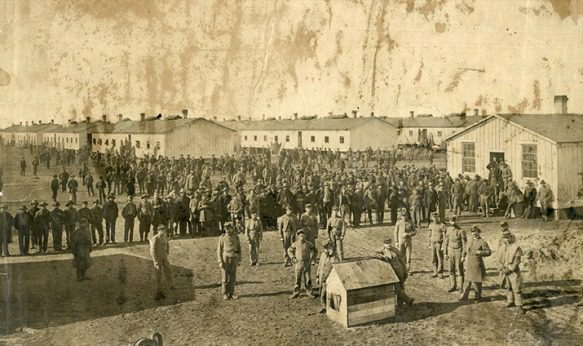

The Democratic newspaper Chicago Times was one of the nation’s most vocal critics of the war. In June 1863, the Union Army forcibly shut it down. The shutdown was short-lived, however, as Lincoln ordered the army to cease its suppression of the paper. Despite this, tensions grew. During the 1864 election, Republicans accused Democrats of plotting with Confederate spies to free Southern prisoners from a local POW camp to disrupt the election. Additionally, a race riot occurred at Camp Douglas in 1862 after white teamsters prevented African Americans from using the omnibus system, which led the City Council to vote to segregate public schools.

George Root, the composer and lyricist of the North’s most popular Civil War song, was born in Massachusetts but moved to Chicago and founded the publishing firm Root and Cady. In 1862, at Lincoln’s request, he wrote “Battle Cry of Freedom.” The song was first performed on July 24 at a large war rally in Chicago. The public reaction was overwhelming, and it quickly became a massive hit, inspiring many similar patriotic songs.

Chicago: A Haven for Refugees

Home to prominent and active abolitionists, Chicago quickly gained a reputation as a Republican stronghold that supported Lincoln. During the Civil War, about 20 African American refugees from slavery arrived in the city daily. From 1860 to 1870, the city’s Black population grew by an astonishing 600%. Despite facing opposition, such as the race riots and poor living conditions, the social standing of Black Chicagoans improved during and after the war, leading to the formation of a professional Black class and a vibrant African American community.

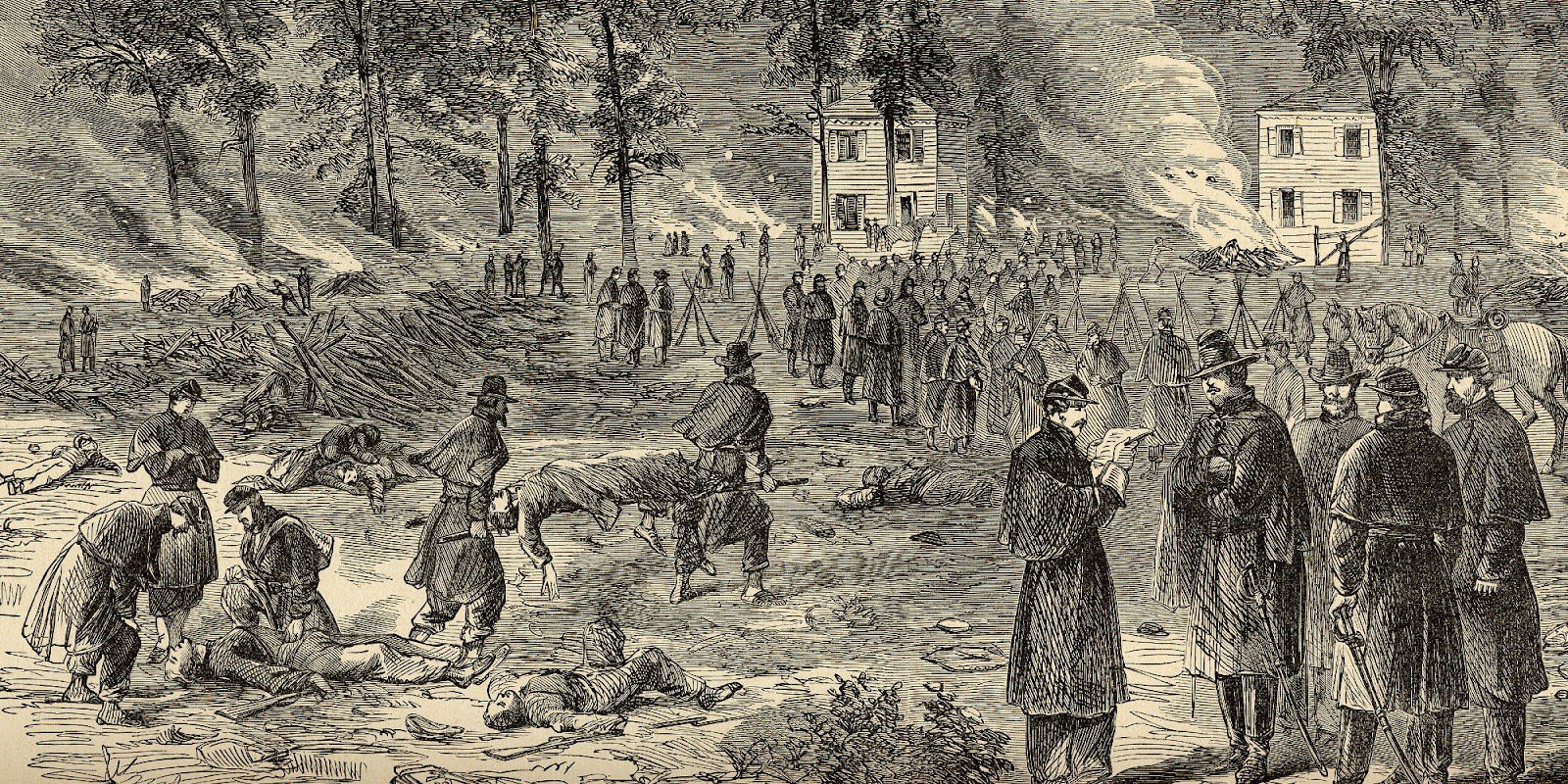

The Role of Women and the Largest POW Camp

The northwestern branch of the U.S. Sanitary Commission, created to improve conditions for sick and wounded federal soldiers, was headquartered in Chicago. Prominent women like Mary Livermore and Jane Hoge organized large-scale fairs where citizens donated goods. These items were sold, and the proceeds were used to buy medicine and supplies for Union troops on the front lines. The 1863 fair was so successful that it inspired similar events across the North.

In 1861, Camp Douglas was established as a training camp for Union troops, named after Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas. In 1862, the camp was converted into a prison for Confederate soldiers captured by General Ulysses S. Grant at Fort Donelson. For a time, it was the largest Union prison, holding over 26,000 men throughout the war. Escapes were common, and during the 1864 election, federal authorities foiled a plot to free prisoners to disrupt the vote. Unlike other Civil War POW camps, Camp Douglas had an exceptionally high death rate, with one in every seven prisoners dying due to unsanitary conditions and the harsh weather.