The Cold War was a period of contained rivalry that developed after World War II between the United States and the Soviet Union. It’s important to note that this conflict was waged on political, economic, and propaganda fronts, with only a limited use of weapons.

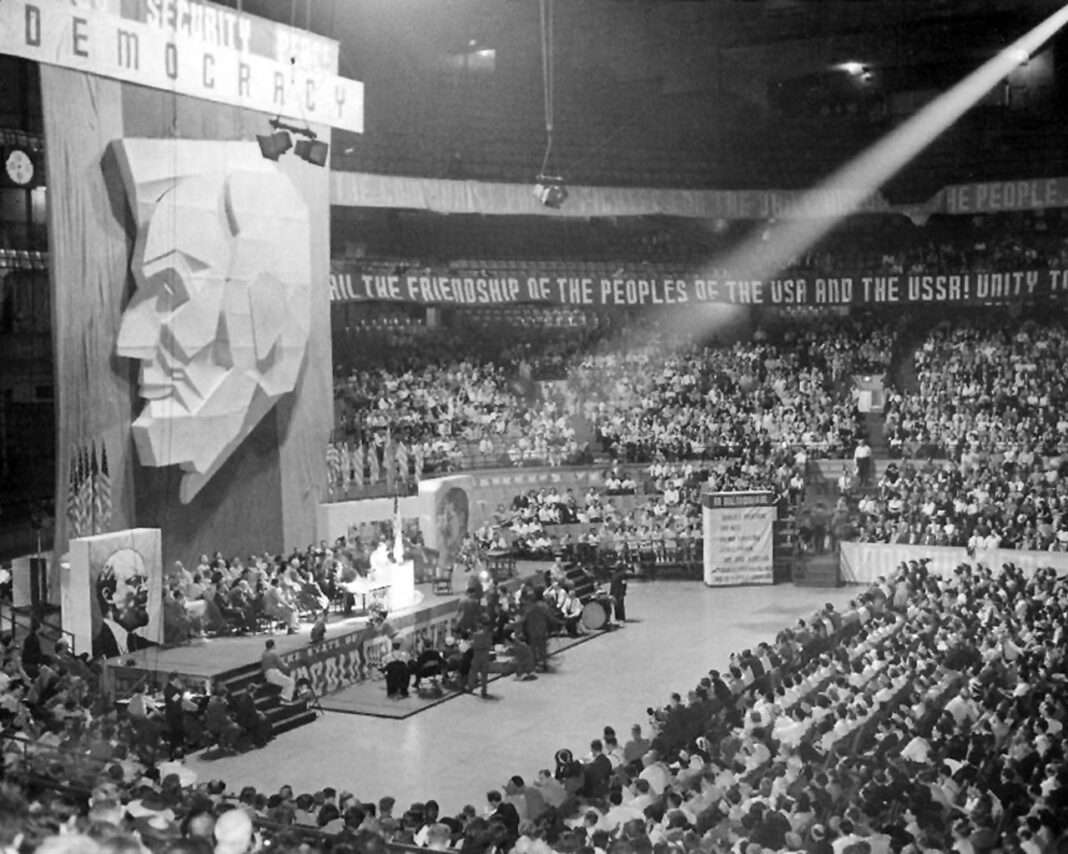

From the late 1940s through the 1950s, the governments of the United States and the Soviet Union were bitter enemies, actively opposing each other in the Cold War. Anti-communism dominated American domestic policy. In Chicago, as in other cities, conservative politicians and city newspapers sought to expose subversive communist activities and actively discredited liberal ideas, writes chicago-yes.com.

The Creation of an Anti-Communist Commission

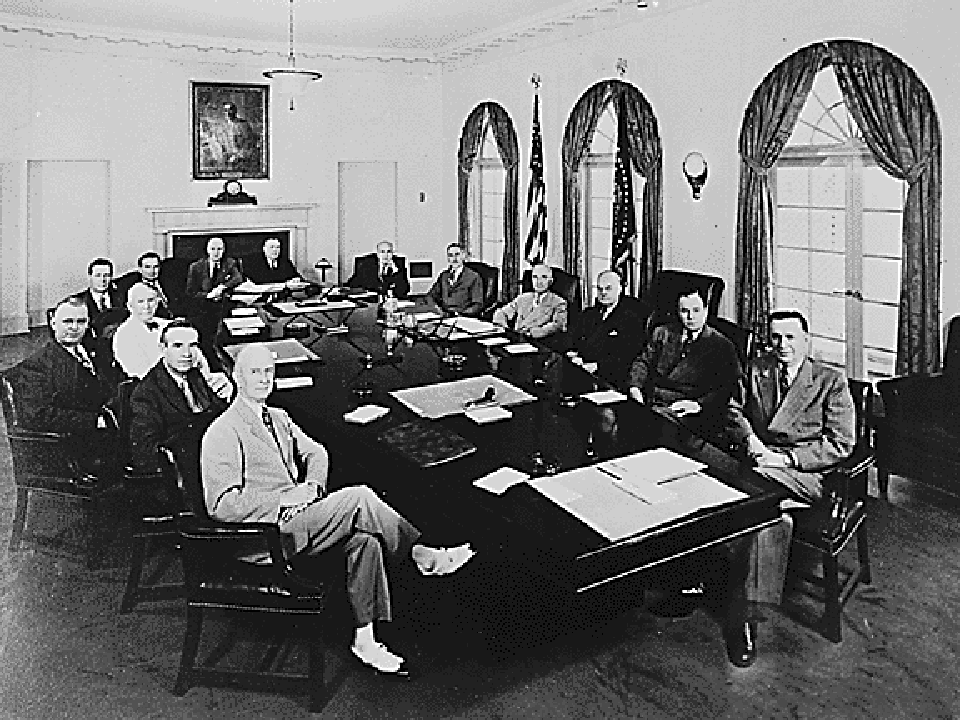

The Cold War reached its peak between 1948 and 1953. Notably, the postwar anti-communist efforts in Chicago were initiated by the Illinois state legislature. In the summer of 1947, it created a commission to investigate seditious activities, known as the Broyles Commission, named after its chairman, Republican State Senator Paul Broyles. It soon determined that the education system was the most vulnerable to communist infiltration. In 1949, the commission held hearings to investigate the political activities of professors at the University of Chicago, but because the faculty was defended by university chancellor Robert Hutchins, the hearings yielded nothing.

Based on the commission’s findings, Chicago’s anti-communists turned their attention to the public schools. Throughout the 1950s, the Chicago Tribune condemned communist rule and campaigned to remove liberal curricula from schools. In the fall of 1950, the president of the Chicago Board of Education, William Trainor, created a committee to study methods for promoting patriotism and combating communism in schools. In 1955, the Board of Examiners began asking teacher candidates to declare their membership in “subversive” organizations and denied certification to some individuals on political grounds.

The Introduction of Loyalty Oaths

Anti-communists also sought to implement a loyalty oath for public sector employees. In the early 1950s, Paul Broyles, supported by the American Legion, authored a series of bills aimed at outlawing the Communist Party and requiring loyalty oaths for state employees. Democratic Governor Adlai Stevenson vetoed these laws, but in the summer of 1955, the new governor, William Stratton, signed a law forcing employees to take the oath. Three Chicago public school teachers refused to sign it. The American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit on behalf of Shirley Lens, one of the teachers, arguing that the oath was unconstitutional. However, the Illinois Supreme Court rejected this lawsuit in 1956.

The Decline of Communism in Chicago

Throughout the 1950s, many people and organizations in Chicago suffered from accusations of communist sympathies. The Chicago Police Department’s “Red Squad” compiled thousands of dossiers on them and obstructed their activities. By the late 1950s, the Chicago Communist Party, which once had several thousand members, had dwindled to just a few dedicated individuals. After it became clear that communism posed no real threat to American society, the anti-communist fervor subsided. However, the Red Squad continued its operations until 1975, the loyalty oath remained on the books until 1983, and the Cold War itself dragged on until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Analyzing these events, one can conclude that the Cold War ruined the lives of many people and made working and living conditions unbearable. Nevertheless, the strong-willed people of Chicago were able to overcome these hardships.