In the first four decades of Chicago’s history, municipal politics were dominated by a wealthy elite. Seeking to improve infrastructure for the city’s future growth, political leaders maintained an appearance of benevolent consensus. However, ethnic and cultural conflicts periodically shattered the illusion of a politically advanced city, as noted on chicago-yes.com.

Early Politics of Chicago

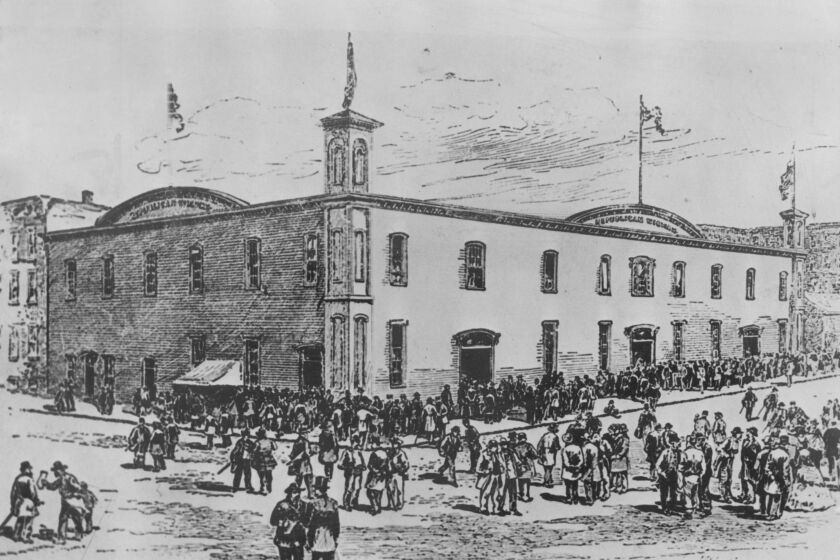

Municipal politics in Chicago emerged after European settlers suppressed the last resistance from Native Americans in the Black Hawk War of 1832. Just a year later, Chicago received its first charter of incorporation. Until the Civil War, as the city struggled to establish itself on the western frontier, there were significant political tensions between elite interests and public needs. Funds were needed to build a strong urban infrastructure—streets, sidewalks, sewer, and water systems. Capital investment was also essential for creating jobs and economic growth. However, in Chicago, the only source of revenue for such projects was property tax. City residents who sought federal assistance for infrastructure projects were rejected by those who preferred private development. This fueled a national conflict between political parties regarding the balance between federal government control and private interests.

Chicago’s complicated relationship with the state of Illinois also defined its municipal politics. American cities derive their governing authority from their respective states. State legislation regulates the relationships between cities and counties, as well as taxation and funding for municipal development. Historically, there was an ongoing power struggle within the state of Illinois, leaving the desires and voices of common people largely ignored. The elite were also slow to inform the public about changes in the political landscape. For instance, in 1893, the state legislature abolished the position of Chicago’s Chief Constable without informing the city for two months.

In the 1850s, social conflicts began to brew in Chicago, gradually introducing ethnic rivalry into the city’s politics. In 1855, residents attempted to regulate the leisure activities of newly arrived German and Irish immigrants by forcing the municipal government to raise the cost of liquor licenses. The resulting riot forced the government to back down, and from that point on, immigrant groups in the city demanded a say in municipal politics, which had previously been controlled by a small group serving their own interests.

Struggle Between the City and the State

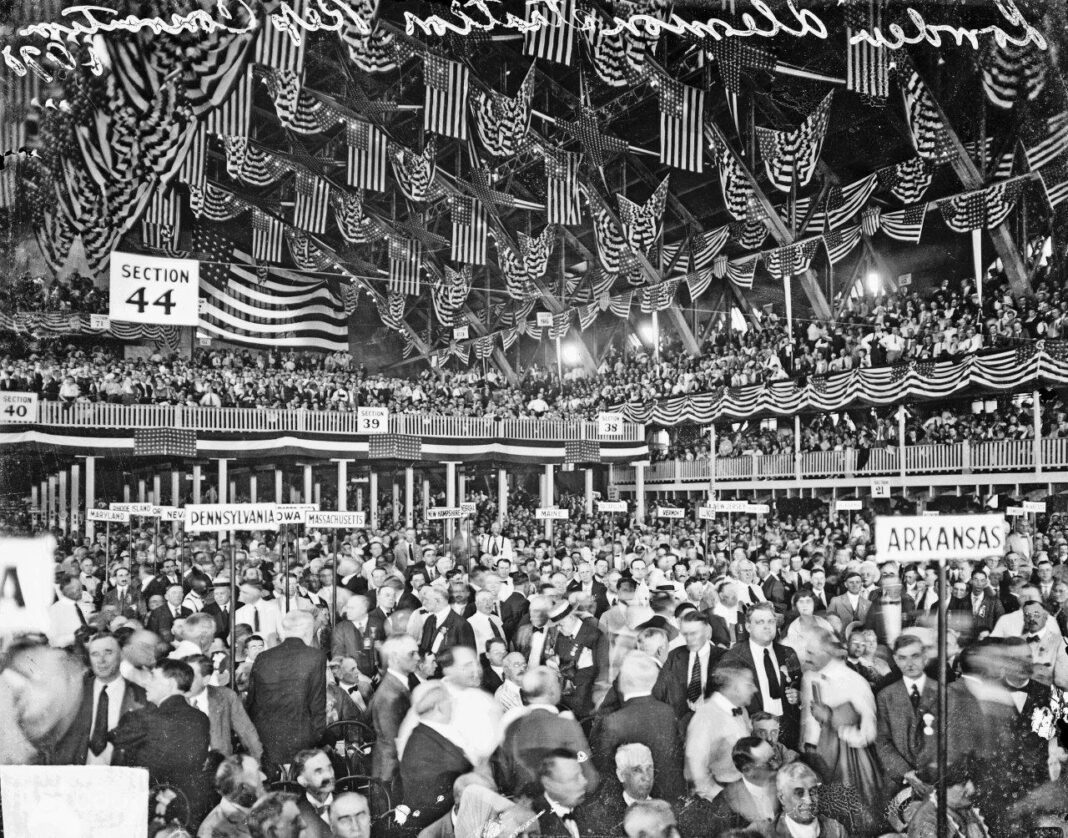

The growing factionalism within the Democratic and Republican parties, along with the ongoing battle between the city and state, defined Chicago politics from the 1870s through the 1930s. These two forces fed off each other as the city developed into an industrial metropolis, straining against the legal constraints imposed by state legislation. In 1872, the state legislature passed the Cities and Villages Act, which applied to all incorporated areas with populations over 2,000.

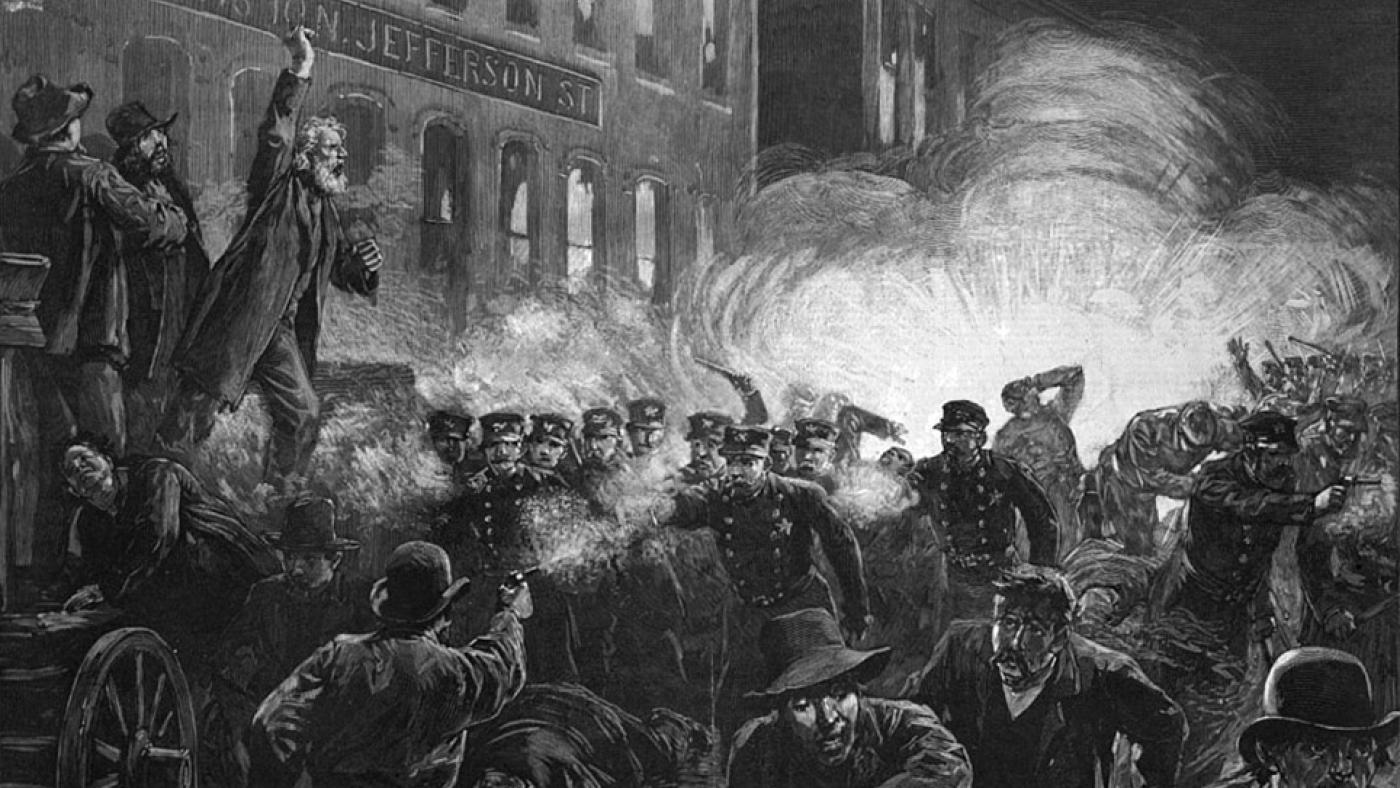

At the start of the 20th century, Chicago sought to improve its standing through legislative efforts to gain home rule. However, each attempt was thwarted by the mistrust between the city and state. Fearing Chicago’s rapid growth and rising influence, the Illinois legislature carefully limited the city’s power. They refused to permit the consolidation of city government and Cook County governance. Efforts at self-government reignited ethnic and class conflicts, leading to political unrest in Chicago, which had flared up before the Civil War and again in 1871, when a group of influential figures tried to seize control of humanitarian relief and the city’s reconstruction after the Great Fire. Chicago’s working class accused these elites of attempting municipal rule—a power grab. This event further divided the city’s residents along class and ethnic lines, and municipal politics became a struggle among the city’s different groups for control of local government in their own interests.

The Rise of Corruption and Women’s Role in Politics

The political struggle in Chicago from the 1870s to the 1930s reflected the broader issues facing the United States, including the exploitation of workers, extreme wealth inequality, and corruption. Political parties in the city functioned as machines, promising services in exchange for votes. Often, their assistance was directed at poor immigrants and businessmen who received permission for potentially lucrative contracts. The parties also became mechanisms for the personal enrichment of politicians. For example, in the 1890s, the “Gray Wolves” faction sold municipal contracts and franchises for street railways and waste collection to the highest bidder.

Public outrage at these practices gave rise to a progressive reform movement in Chicago, but its efforts were largely unsuccessful. Businessmen aligned with the Republican Party argued that reform should bring experience and financial efficiency to the government. In 1907, they unsuccessfully supported a home rule charter, opposed municipal ownership of public utilities, and called for an end to patronage politics, the election of professional experts over party politicians, and a strong mayor to weaken the city council’s power. Ethnic and immigrant groups supporting the Democratic Party opposed these ideas, claiming they were designed to transfer city governance into the hands of middle-class businessmen.

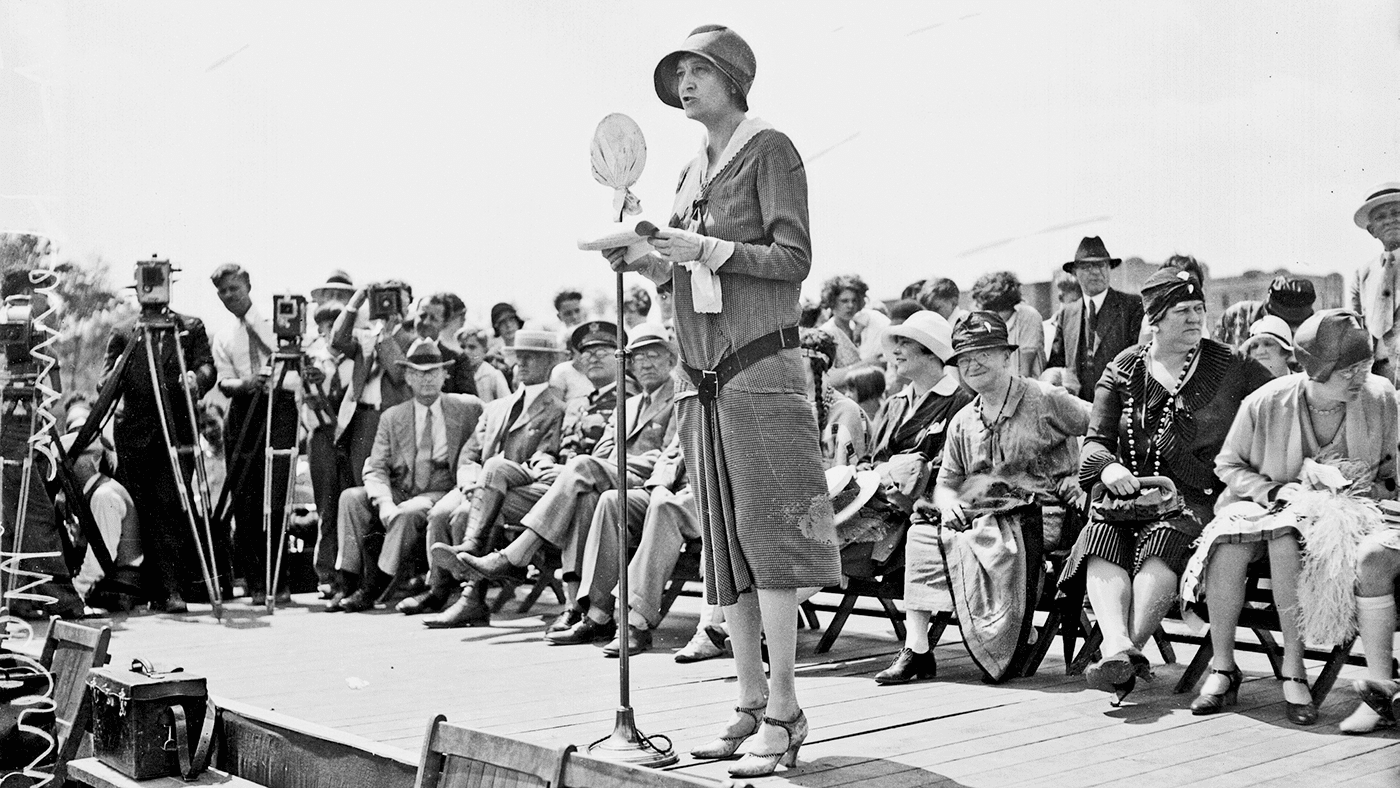

In 1913, women gained municipal suffrage, but they did not easily integrate into Chicago’s political scene. Neither the Democrats nor Republicans made efforts to secure women’s loyalty to their parties, and women remained largely excluded from political life. Both parties refused to nominate women for municipal office, and male voters did not support female candidates.

In 1916, Mayor Thompson removed the Commissioner of Public Welfare, a significant political defeat for women. No woman was elected to the city council from that time until 1971.

A New Era of Politics

In the 1930s, a new phase in Chicago politics began. Democrats gained access to funds and programs for housing, slum clearance, urban renewal, and education. Mayor Richard J. Daley (1955–1967) helped secure the city’s financial well-being and that of the Democratic Party by gaining more control over municipal services. Together, they shaped Chicago’s policies by leveraging the growing racial and class divides. To drive the city’s development, Daley secured lucrative contracts, created favorable conditions for real estate purchases and taxation, and launched an urban renewal program that primarily benefited the middle class and business elite. The election of Richard M. Daley as mayor in 1989 marked the beginning of a new era in Chicago politics. He continued Harold Washington’s initiatives, making city politics and governance more inclusive in terms of race and gender, with a focus on Chicago’s economic development.