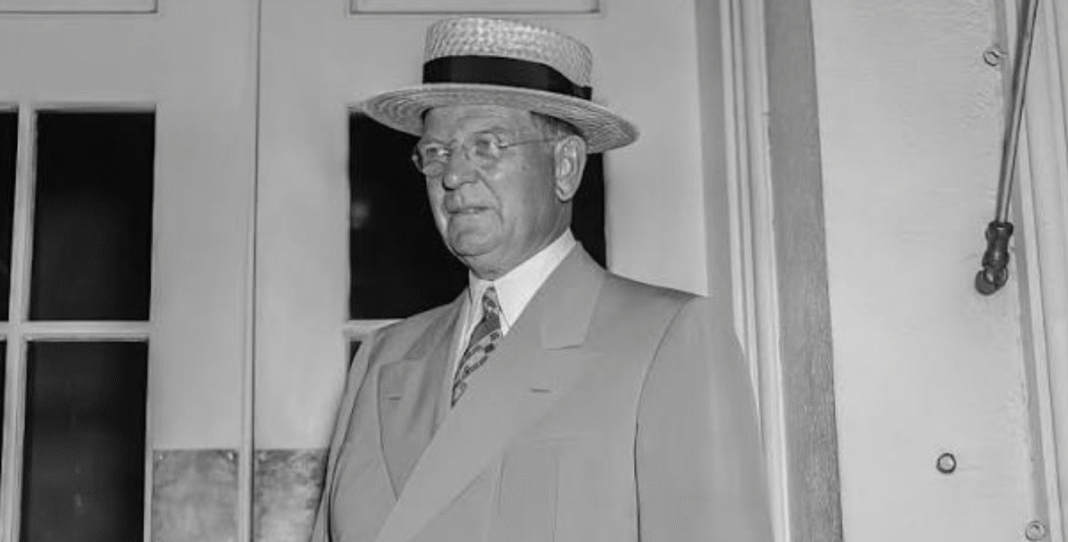

Edward Kelly is remembered in Chicago history as one of the most influential mayors, leading the city during the challenging periods of the Great Depression and the second decade of the 20th century. His political tenure combined transformative reforms and administrative decisions that changed the city while cementing the Democratic Party’s role in Chicago politics. Learn more on chicago-yes.

Biography

Edward Kelly was born in Chicago to police officer Stephen Kelly and Helen (née Lang). Kelly did not finish high school and began working at the age of ten. By the 1920s, he had become the chief engineer of the Chicago Sanitary District. His career gained momentum thanks to the support of Patrick Nash, a contractor whose company worked closely with the city administration.

The Path to Politics

In March 1924, Kelly was appointed President of the South Park Commission, the body that governed parks and sports facilities on Chicago’s South Side. He declared an end to the era of the “Deenen Republicans,” the conservative faction of South Side Republicans who had previously controlled the commission.

Under his leadership, the construction of Soldier Field was completed, establishing it as the city’s primary sports arena. Kelly organized public events, charitable galas, and supported organizations affiliated with the Democratic Party.

Mayor of Chicago

Following the assassination of Mayor Anton Cermak, Kelly was selected for the mayoral office with the backing of the Democratic Party and Patrick Nash. Together, they established the formidable “Kelly-Nash Machine,” known as one of the most powerful political organizations in a major U.S. city.

During Kelly’s tenure, the city received a significant boost from New Deal programs. Federal money, channeled through the WPA (Works Progress Administration), was used not only for the subway but also for roads, school buildings, and housing. This funding allowed Kelly to sustain his political machine—he utilized the federal programs to create jobs and maintain his party’s influence. According to New Deal records, a large portion of WPA workers were employed on Chicago projects, which also reinforced the public legitimacy of the Kelly administration.

Early in his term, Kelly emphasized Chicago’s water system: he signed a letter of welcome to city waterworks engineers during the “Century of Progress” (World’s Fair) celebration, describing the water system as one of the cheapest among large cities. A 1933 Chicago booklet, signed by the mayor, noted that Chicago’s municipal water system provided water not only to residents but also to neighboring cities at highly competitive rates—illustrating Kelly’s drive to make the city’s infrastructure modern and accessible to the public.

In 1946, following criticism from the National Education Association (NEA), Kelly formed an advisory committee led by Henry Townley Heald (the Heald Committee) to reform the city’s school system. The committee recommended replacing some school board members and restructuring the appointment process. Most recommendations were accepted, though Kelly disagreed with the blanket dismissal of all board members—nevertheless, several did resign. This system became part of what cities later referred to as a “legal” mechanism of appointment, influencing how the school board was structured even after his term ended.

Kelly was a strong supporter of the “Century of Progress” World’s Fair, which was held during the Great Depression. He initiated the hosting of the first official Major League Baseball All-Star Game during the fair, which became a symbol of the city’s cultural and athletic revival.

Kelly and Patrick Nash built a powerful Democratic political organization (“Kelly-Nash Machine”) that merged party resources with business support. According to “TIME” magazine, critics called Kelly the “City Boss”—he actively used his power for patronage and to maintain political control, even amid the system’s corrupt characteristics. Kelly was also known for his firm stance on cultural content. For instance, he banned Nelson Algren’s novel *Never Come Morning* from the Chicago Public Library following protests from the local Polish community.

Legacy

In 1947, Kelly voluntarily stepped down from the mayoral office, yielding the spot to Martin H. Kennelly, a candidate with a reputation as a reformer. Afterward, he remained active in the Democratic Party of Illinois.

Edward M. Kelly died in 1950 at the age of 74 and was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Evanston, Illinois. His work earned expert recognition: in 1994, he was included among Chicago’s top ten mayors.

Edward M. Kelly left a significant imprint on Chicago’s political and municipal history. His reforms in transportation, education, and the development of the city’s sports and cultural infrastructure helped Chicago overcome the effects of the Great Depression and strengthened the Democrats’ hold on the South Side. His legacy demonstrates how the combination of political leadership, administrative reforms, and cultural influence can transform the face of a metropolis.