According to historians, Chicago’s politics are a national cliché, conjuring images of a one-party system dominated by a boss-controlled Democratic political machine. In this system, cunning politicians offer patronage to competing ethnic and racial groups in exchange for votes. For more on the city’s politics, check out chicago-yes.com.

Corruption Without Consequences

It’s widely known that no political, ethnic, class, or gender group in Chicago and its suburbs has been immune to the allure of patronage politics or the stain of corruption. When reform-minded Republicans took control of the Common Council in the late 1890s, they behaved just like the Democrats they had ousted. The Republicans replaced all appointed officials with their own supporters—the very practice they had condemned when Democrats used it.

Women in the city entered the political fray after gaining municipal suffrage through an Illinois law in 1913. In 1915, Mayor William Thompson dismissed the pleas of a delegation of women’s public-interest advocates, led by Mary McDowell, who were pushing for an experienced woman to be appointed to the new position of Commissioner of Public Welfare. However, Thompson soon appointed a woman to the role—but chose an inexperienced Republican activist named Louise Rowe. A year later, she resigned after being accused of orchestrating a fraudulent scheme within the welfare department.

While no mayor has ever been convicted of illegal activities, several have been implicated in questionable campaigns and corruption scandals. Republican mayoral candidate Fred Buss was accused of distributing jobs, money, and coal from his coal company in exchange for votes during the 1907 election. William Thompson was persuaded not to run for re-election in 1923 amid a series of scandals, including issues in the public schools and accusations of blatant political manipulation during the nomination of county court judges. Mayor Ed Kelly also gained notoriety for graft and bribery during his time as chief engineer of the Metropolitan Sanitary District, though he later managed to escape any consequences. Even the honest mayors had to tolerate corruption. A prime example is Martin H. Kennelly, who brought order to the school system and modernized the city’s administrative practices. However, he couldn’t end political influence in the police department or support his appointee to head the Civil Service Commission when that person tried to gain control of hiring patronage.

The politics of “honest graft” were famously shaped in New York by George Washington Plunkitt. In Chicago, prominent city council members, high-ranking municipal officials, and even the mayor’s press secretary were accused of extortion in exchange for jobs and, more generally, of using their positions in city government for personal gain. These events are a fascinating and undeniable part of Chicago’s political history.

The Struggle Between Private Interests and Public Needs

Chicago’s politics are also characterized by the growth and development of American cities, a struggle for democratic governance that unfolded within the federal legal system and political structure. The city’s municipal politics began after European Americans suppressed the final Native American resistance in the Black Hawk War of 1832. By 1833, Chicago had already received its first charter from the state legislature. During the Civil War, as white Chicago settlers fought to establish the city on the western frontier, politics became a battle between private interests and public needs. Funds were desperately needed to build urban infrastructure—streets, sidewalks, sewer, and water systems—and to support new commercial activities. This would create additional jobs and ensure economic growth. However, Chicago could only fund these activities through property taxes, which residents were reluctant to pay. Private individuals skillfully exploited the meager public funds, such as in 1837 when the Cook County School District Commissioner lent the school fund, raised from the sale of federally donated land. Chicago residents who wanted federal government assistance for infrastructure projects were hindered by those who favored private development. This local conflict mirrored a nationwide struggle between political parties over whether the public’s need for a federal government should prevail over private interests. Notably, private interests were prioritized before the Civil War.

Party Disputes

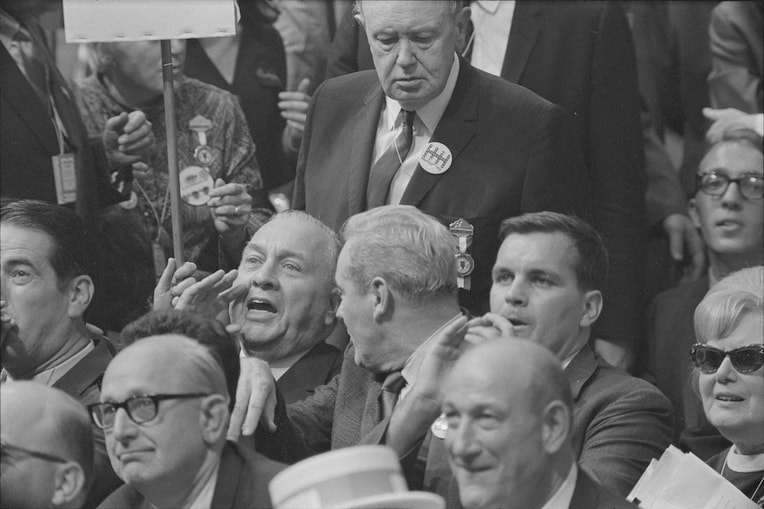

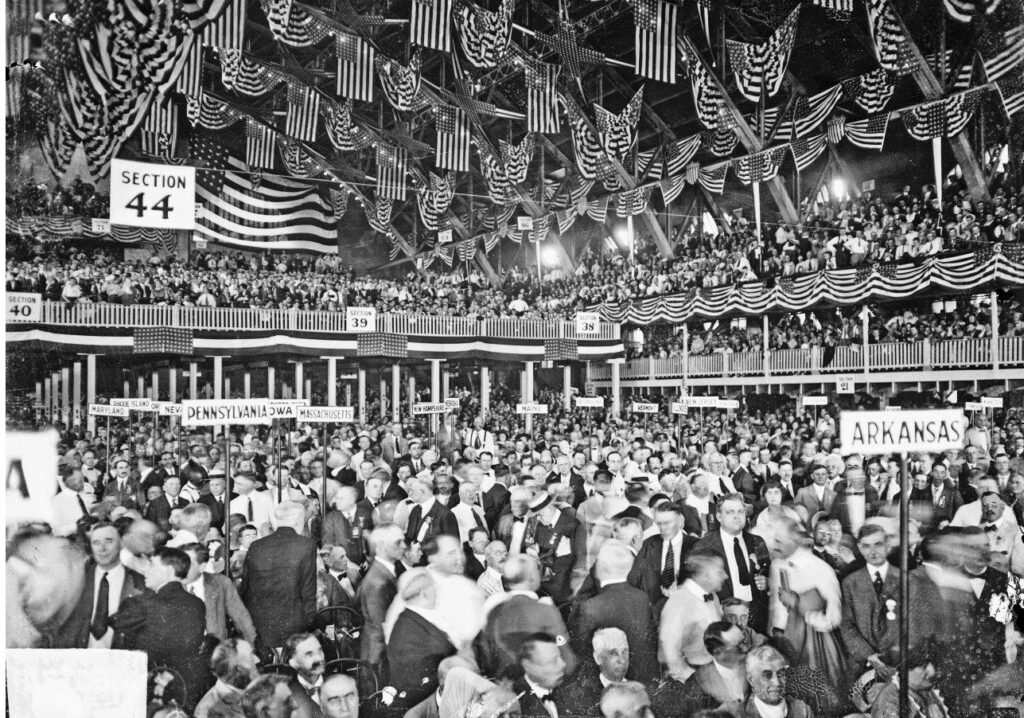

In the 1870s, Chicago saw a political battle that reflected nationwide issues. It was a period of re-evaluation for the nature and goals of democratic governance. Rural Midwesterners, African Americans from the South, and Mexicans joined hundreds of thousands of European immigrants who arrived in Chicago seeking better economic, political, and social opportunities. However, worker exploitation, extreme wealth and poverty, and corruption among businesspeople and politicians were rampant in the city. The reason for this was that neither federal nor local authorities could stand up to the worst aspects of economic and social injustice. In the absence of such authority, political parties operated as machines that promised to provide services in exchange for votes. The parties were also machines for enriching politicians, as seen in the 1890s when the infamous “Gray Wolves” group of aldermen sold municipal contracts for streetcar railroads and garbage collection to the highest bidder. Public outrage over this led to a progressive reform movement, yet no agreement on reforms was ever reached. Republicans believed that any municipal reform should promote a higher level of professionalism and financial efficiency in government. They also demanded an end to patronage politics, the election of expert civil servants rather than party politicians, and the implementation of a strong-mayor system that would weaken the city council’s power. Democrats opposed many of these ideas, arguing that they were designed to put city government into the hands of middle-class businessmen.

Women did not fit into Chicago’s party politics. Neither Democrats nor Republicans made any serious attempts to secure their party loyalty. Therefore, women remained detached from the city’s political life. The parties were also vehemently against nominating women for municipal office.

In 1931, Anton Cermak won the mayoral election with the support of minorities and the working class, securing Democratic Party dominance. Meanwhile, the Republican Party self-destructed as progressive and liberal Republicans grew to resent the party’s support of Mayor William H. Thompson, whom they considered a proponent of ethnic politics. His campaigns included crude ethnic slurs and a willingness to change sides on any issue if it served his goals. The decision by party leaders to back Thompson for re-election in 1931 was the last straw for prominent Republicans, and many of them supported Anton Cermak instead.

Democratic Party Leadership in Chicago

The New Deal of the 1930s and the Great Society of the 1960s gave the Democratic Party access to new funds and programs for housing, slum clearance, and more. Mayor Richard J. Daley also supported the financial stability of the city and the party.

Richard Daley and the Democrats controlled Chicago’s politics by exploiting growing racial and class antagonisms. From the 1940s onward, African American and Hispanic populations competed for jobs, housing, and schools. Middle-class white residents fled to the suburbs, while Democrats maintained the support of working-class ethnic whites. This led to social and economic segregation in neighborhoods, housing, jobs, and schools. Selecting loyal Black politicians for municipal office who could provide jobs ensured the loyalty of African American voters to the Democratic Party well into the 1970s. To make Chicago a city with many job opportunities, Mayor Daley engaged the business community by contracting new projects. He also structured profitable real estate and tax savings deals, as well as an urban renewal program that benefited the middle class and businesspeople more than the city’s poor.

In the late 20th century, Chicago saw a brief surge in African American influence, embodied in the two elections of Harold Washington. But this momentum faded, and Richard M. Daley was elected mayor. Under his leadership, Chicago’s politics changed. He continued Washington’s ideas, making governance more inclusive racially and gender-wise. He also expanded upon his predecessor’s idea of prioritizing the city’s economic development. However, the revelation of lucrative deals and contracts being handed out to friends and Democratic Party supporters shows that patronage politics have become an inseparable part of Chicago’s life and are unlikely to ever disappear.